Kathy likes movies about a long lingering death of a loved one. My movies involve, Charles Bronson or Clint Eastwood or someone like that who is badly wronged in the beginning of the movies and then he kills people all through the rest of the movie to get even. The children's version of this would be Mighty Mouse.

Why do I find this kind of movie so satisfying? I began to get some insight into this question about ten years ago. Near the time it first came out, I read a book called Violence Unveiled: Humanity at the Crossroads by Gil Bailie. It is one of a dozen books I have read that immediately altered my view of the world. Since I read that book, I see many social relationships, including my own, in a different way.

This book is actually a popularization of a philosopher, Rene Gerard. Since reading Bailie's book, I have read books by Girard himself, but I find them heavy lifting, so I mention Bailie's book first. This is a theory about why people act like they do.

Bailie, following Girard, supports the theory by giving examples from anthropology and literature. Let me describe my simplification of Bailie's simplification: People, from the time we are little babies, must imitate other people. We see someone else and we want to act the way he acts, look the way he looks, have the things he has. We must do this because this is the way we learn and become older human beings--it is part of the essence of being human. So every healthy, whole human being begins with this desire. Bailie calls it "mimetic desire."

What is "mimetic?" It just means someone is apt to imitate. A snake that looks like a poisonous snake, but is harmless, but survives because it looks like the poisonous snake is a mimetic animal. It comes from a Greek word that means "imitate."

In most ways the mimetic desire is something good for society, especially when it involves copying knowledge or copying values:

The English teacher recites Shakespeare and now all of his students want to recite Shakespeare.

Dad is kind to beggars and now his children are kind to beggars.

When it involves a desire for other people's stuff, it is a little less attractive:

On a simple childhood level, one kid has a toy. Another kid wants to take the toy away from him, but when the first kid loses interest in the toy, they both do and it sits in the middle of the floor where neither plays with it.

One young lawyer drives an expensive sports car, so his buddy wants an expensive car too.

Move on from things to treating people as objects, and it can get really nasty:

The young woman is more attractive to her husband's friend when she is married than after she is divorced. "If he wants her, I want her too, but if he doesn't want her, there must be something wrong with her and I'm not interested."

John Lennon is rich and famous and I'm not so I guess I'll kill him.

Mimetic desire can also be more generalized, between people who identify themselves with groups and with a risk of a bigger level of violence:

The Dutch own all of the property and we want some property.

Mexican immigrants are taking jobs and we want those jobs.

The Jews own all of the banks and newspapers and we want the banks and newspapers.

So, we have mimetic desire both among each other within a group and generalized between group.

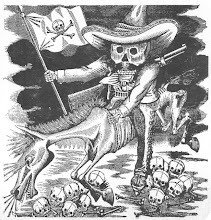

Bailie says that one way that people within groups work out their own risk for violence arising from mimetic desire is to find a scapegoat to sacrifice. This scapegoat can be literal, in the sense of animal sacrifice, or it can be metaphorical, in the sense of picking out an individual and throwing him out of the group. He then takes the blame for all of the problems the group was having and there is a period of peace.

An example of this in daily life would be a workplace in which everyone is fighting. Someone gets fired and then everyone can blame the scapegoat for all of the problems. A period of peace reigns.

A classic political example is Hitler's use of the Jews as a scapegoat for disputes among the German people. By sacrificing the Jews, we have someone to blame for all of our problems and now we can get along.

Many political efforts at unifying a generally violent community involves finding the scapegoat to blame, so the rest of us can mend our differences: Muslims, homosexuals, communists.

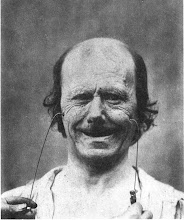

How does the act of violence against one outcast bring the others back together? Bailie illustrates this with a story of a wise man who was asked to heal the community of a generalized plague of violence. The wise man finds a beggar and tells the mob who have been fighting each other that the begger is a demon. At first, individual members of the mob resist, but then someone throws the first stone. Soon, everyone else pitches in and they stone the beggar into an unrecognizeable bloody pulp. The wise man then says, "See, it was not a beggar, but a demon. Now it has transformed into a bloodied Milosian Hound."

Everyone's guilt is assuaged because they know they have not killed a innocent beggar, but a demon, now transformed into a hound. Also, the act of violence against the beggar allows the mob job to join in a common cause rather than fighting among themselves. The plague of violence in the community comes to an end, at least for a while.

Bailie contrasts this solution with Jesus' solution to a plague of violence in which Jesus himself becomes the beggar and the Milosian Hound, but allows the mob to see the violence from His point of view. The myth of sacred violence is then exposed for what it is--injustice.

Back to Clint Eastwood and Mighty Mouse. My generalized anger towards others who either have something I want or want something I have can be calmed for a while watching the movie.

Clint and Mighty Mouse are the good guys. By stoning some Milosian Hounds we can all feel better for a while.

This also explains why prisons and the death penalty can make the rest of us feel better for a while.

_-_Dante_And_Virgil_In_Hell_(1850).jpg)

2 comments:

Seen that type of behavior yesterday at the convention. Interesting post.

Right on, Ed. You show how close to home mimetic desire is, first person singular.

We're living in highly mythic and superstitious days -- which seems strange given the simultaneous heightened glories of technology -- and dangerous. Cheers

Post a Comment